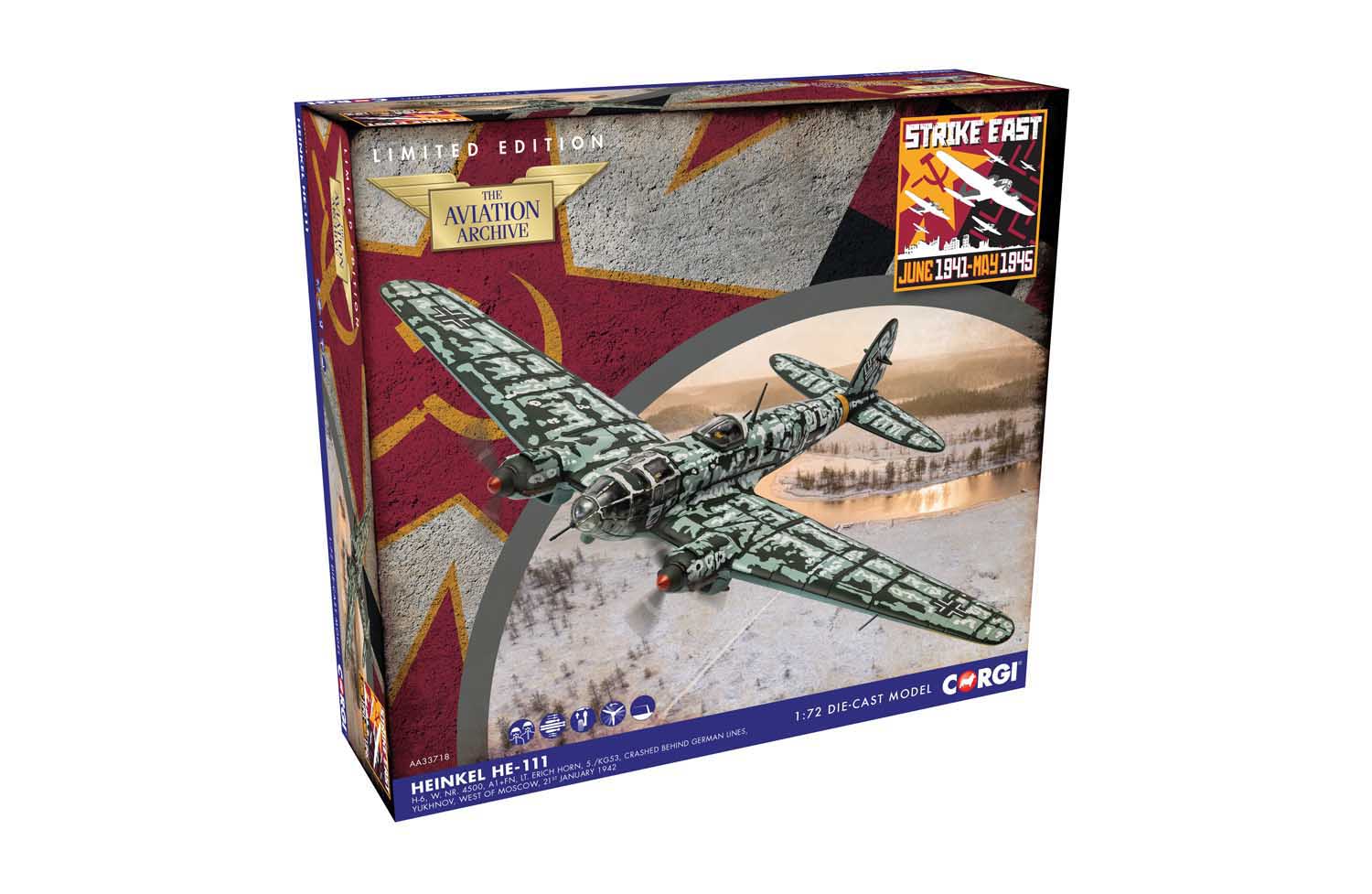

Heinkel He-111 H-6, W. Nr. 4500, A1+FN, Lt. Erich Horn, 5./KG53, Crashed behind German Lines, Yukhnov, West of Moscow, 21st January 1942

Heinkel He-111

H-6, W. Nr. 4500, A1+FN, Lt. Erich Horn, 5./KG53, Crashed behind German Lines, Yukhnov, West of Moscow, 21st January 1942

If the Messerschmitt Bf 109 was the most famous Luftwaffe fighter aircraft of the Second World War, then its direct bomber equivalent had to be the Heinkel

He-111, an aircraft which can trace its origins back to the early 1930s and its development as a supposed fast civilian airliner, due to the restrictions imposed

on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. Once the country was no longer concerned with the pretence of trying to plicate the other European powers, the

Heinkel showed itself to be a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ and thanks to its large, fully glazed ‘greenhouse’ nose, would become one of the most famous aircraft

of WWII. Possessing greater range than other Luftwaffe strike aircraft, the Heinkel He-111 would see heavy use during Operation Barbarossa and the air

battles which raged over the Eastern Front from 1942 onwards, but not always in its primary strike role. Due to the rapidly deteriorating situation for the

Germans, Heinkel He-111 bombers were also used for casualty evacuation and re-supply duties, where they would supplemented the efforts of the lumbering

Junkers Ju-52 Trimotors. This particular Heinkel has added rather effective whitewash blotches over its standard camouflage, something which would have

looked rather effective against the frozen Russian tundra from above. Whilst attempting a low level bombing attack against targets in the Kaluga area, south

of Moscow, this bomber was hit by accurate Soviet anti-aircraft fire and was forced to crash land, thankfully for the crew, safely behind German lines.

Although the Soviet High Command had a strong mistrust of the Germans, they did not necessarily want to do anything militarily that would provoke them into

an attack. Also, despite the fact that their massive air force was coming towards the end of a significant period modernisation and reorganization, this work

was still ongoing and on the eve of Operation Barbarossa, even though more modern aircraft were now slowly being introduced, pilot conversion and the

general organisation of the force still left much to be desired. With Soviet airfields in the Western districts regularly undergoing air raid drills, when the sirens

sounded in the early hours of 22nd June 1941, few on the seventy-six airfields identified for attack by Luftwaffe aircraft that morning actually took any notice,

with crews remaining in their tents sheltering from the rain, only rushing to their posts once the explosions started. These early Luftwaffe strikes proved to be

devastatingly effective, with reports sent back to headquarters later claiming almost 1500 Soviet

aircraft destroyed on the ground alone, figures which seemed so incredible that Herman Goering

had them independently verified.In fact, the figures proved to be a little conservative and as

German ground troops overran numerous Soviet airfields during their lightning

advance, it became clear that this figure was actually well in excess of 2000

aircraft destroyed. In the air it was a different story and despite flying

obsolete Polikarpov I-15 and I-16 fighters, Soviet pilots proved to be

tenacious and brave, resorting to ramming their German foes if

they could get close enough. This would prove to be the sign of

things to come and whilst initial German victories were indeed

spectacular, the Russian winter and the nation’s manufacturing

prowess and fighting spirit would soon turn the tables in their favou